As I get older, I get a little existential about political opinions. The opinions I have now seem sensible, but I understand they’re also products of the evolution I’ve undergone as a man who’s been alive for four decades. In some ways I’m more dumb and uncertain at 40 than I was at 25; in other ways I’m more smug and condescending. Though I’d like to think I’m mostly smug and condescending about the virtues of admitting you’re dumb and uncertain.

I started identifying as a “conservative” when I was in high school, which meant opting into a certain set of conclusions that were byproducts of that particular context. This was in the late 90s, the epoch of boomer liberalism on this continent, a time when many young conservatives were motivated by a youthful contrarianism that saw continuity between the bossy liberal authorities in their lives and the ones assumed to be in power elsewhere. A line from the history teacher to Al Gore.

My first year of college was the first anniversary of 9-11, and I remember observing a student union vigil where they ostentatiously declared their memorial was also for the thousands of Chileans who had perished under the American-backed dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, whose coup happened on September 11, 1973. Theatrical anti-Americanism of that sort was threatening to my fragile faith in American exceptionalism, and like most conservative undergrads, I extrapolated campus spectacles of this sort as reflective of larger ideological trends within the elite.

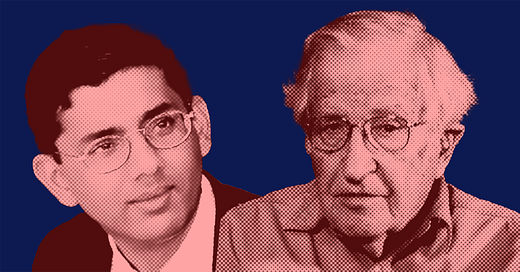

College kids tend to be hungry consumers of political writing, and often display great credulity for any author with a pretense of provocation. I remember reading Dinesh D’Souza’s Letters to a Young Conservative (2002) around this time — a book heavy on the “conservatives-are-the-real-rebels” theme that’s so prevalent now — and finding his arguments exhilarating. Today, I understand that 9-11 vigil as just a different manifestation of my own appetite for youthful contrarianism, in this case fed by “dissident” leftist authors like Noam Chomsky whose simplistic theories of propaganda and war scratched the itch of others.

A lot of the political culture of our current moment is defined by mass seduction to this sort of political novelty. We’re all college kids now. The internet has made it easy to spread information to a greater variety of people, including a great many who might not have otherwise encountered the Noam Chomskys and Dinesh D’Souzas of the world.

Democratization of knowledge produces a true “marketplace of ideas” online, where the most enticing ideas enjoy great popularity. What makes a belief enticing, in turn, seems to be some mixture of comprehensiveness (does it provide a lot of answers), intuitiveness (does it feel correct based on what you already know), flattery (does it make you feel superior for knowing), and relevance (does it allow you to do something in the real world). Beliefs and belief systems that check these boxes are very attractive when we’re young, because they can provide a shortcut to many of the things we crave in early adulthood — certainty, confidence, authority, independence — but the modern world has shown that a lot of people crave those things later in life as well.

It’s also true that American culture in general has gotten very political lately, and this begets pressure to participate in political debates and comprehend media with political themes.

The outcome has seemingly been an explosion of people suddenly concluding they’re alt-right, or far-left, or fundamentalist Catholics, or goldbugs, or anti-zionists, or some other identity offering a theory of everything. Oftentimes, these people will proudly tell you that they “weren’t into politics” until very recently. They have what is sometimes called the “convert’s zeal.” Trump in particular seems to have both assembled, and is seeking to broaden, a coalition of people who (like himself) haven’t historically thought much about politics but now have the convert’s zeal about the uniparty or great replacement or whatever.

A lot of Trump supporters bring out my condescending side, as do a lot of the far-left people on TikTok heaping praise on Osama Bin Laden or the Unibomber for their “brilliant observations.” I know they will one day age out of thinking like this, because these beliefs are silly and simplistic and life will eventually expose them to complicating facts that will humble them.

Someday enough people will be humbled that it will be cool to be nuanced and even-tempered and modest, to be pragmatic and utilitarian, and judgemental of anything that reads as crankish or conspiratorial. We’re far from that now, but it will happen someday, because that’s how these things go.

The four-sided framework which you proposed of comprehensiveness, intuitiveness, flattery, and relevance offers interesting way to understand belief formation.

I sure hope you're right about that last paragraph there but its hard to be optimistic about that in the current climate.